Study of Macro

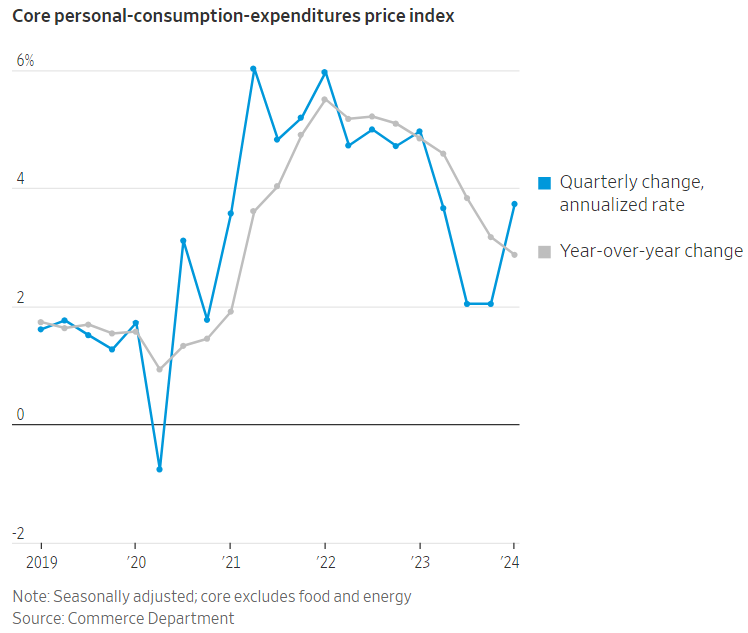

Before the GDP report, Wall Street had forecast a 0.3% increase in both the headline and core personal-consumption-expenditure indexes in March. The March report comes out Friday morning.

Yet if taken at face value, the GDP report suggests both indexes could show gains of either 0.4% or 0.5%. That’s worse than the Federal Reserve or investors had expected.

Such large increases would also suggest inflation is no longer slowing, and perhaps worse, that it might even be on the rise again. The Fed is trying to get the rate of inflation down to 2%.

What’s more, another poor PCE report could push Fed rate cuts to the early fall — or even further out.

Some analysts are skeptical the March PCE report will be so negative.

They point out that the PCE report is derived in part from previously released surveys of consumer and wholesale prices. Neither the consumer-price index nor the producer-price index in March hint at 0.4% or 0.5% PCE readings.

“Such a large miss for March seems implausible, as one can typically estimate month-to-month core PCE inflation to within a few basis points based on the CPI and PPI data for the month,” economists at Bank of America wrote in a note.

What’s more likely, economists say, is that the government revises up the PCE inflation readings for January and February.

Does it matter?

Investors and the Fed already know inflation picked up in the first two months of the new year. The core PCE index jumped 0.3% in February and 0.5% in January after hardly any increase in the last three months of 2023.

If the January and February numbers are revised higher and the core reading in March comes in at 0.3%, it would at least be a sign that inflation didn’t get any worse last month.

Not that it would be of great comfort to investors, consumers or businesses that had been expecting rate cuts this year.

“Even if the March PCE inflation measures rise just 0.3% when reported tomorrow, as expected, they will be accompanied by upward revisions to January or February,” said chief economist Chris Low of FHN Financial. “As a result, as we already know from the [GDP] numbers reported, inflation in the quarter was ugly.”

- 04/25/2024 – The Dream of Fed Rate Cuts Is Slipping Away – WSJ

inflation was stronger-than-expected during the first quarter. Core prices, which exclude volatile food and energy items, rose at a 3.7% annualized rate during the quarter and were up 2.9% from a year ago, according to the personal-consumption expenditures price index.

Price data for March will be released by the Commerce Department on Friday. Thursday’s report suggested that figures for January and February are likely to have been revised higher from already firm levels and that inflation didn’t ease and may have picked up in March, keeping the 12-month inflation rate around 2.8%.

Omair Sharif, founder of research firm Inflation Insights, said he believed revisions to seasonal adjustments could explain some of the likely revisions to inflation in Friday’s report.

Others have said a stock-market rally fueled by rate-cut hopes late last year may have boosted prices for financial-management services that feed into the inflation gauge.

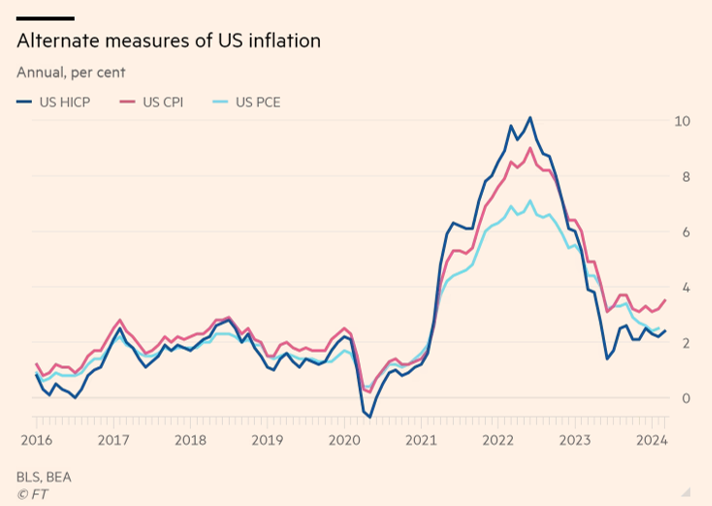

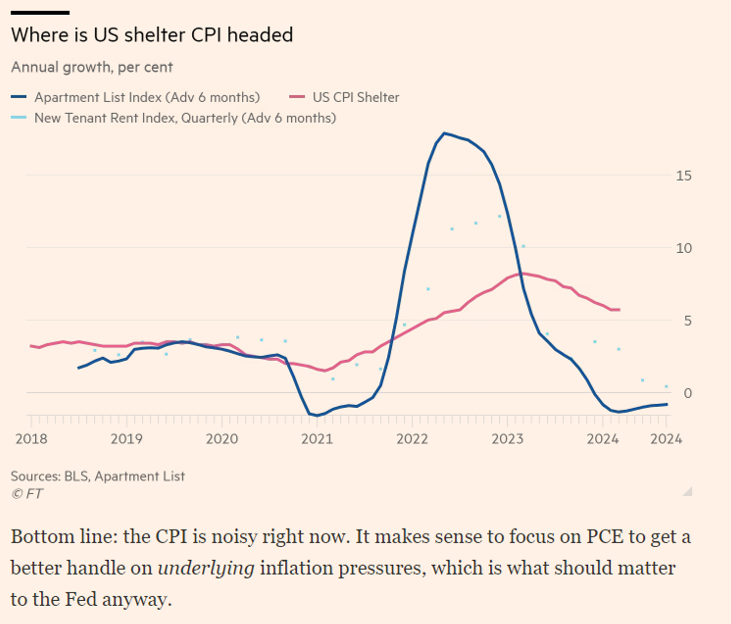

A contrarian take on the US inflation freakout

How does the Consumer Price Index account for the cost of housing_ _ Brookings

- 04/20/2024 – Fed report highlights risks to financial stability if interest rates stay higher for longer (msn.com)

- 04/20/2024 – Subs: Credit – ValuePlays

Now, I get these are low historically and currently no reason to be concerned. BUT, they do now need to be watched as they have been moving higher over the past year. Credit card losses are now at 3.6% vs 3.07% last year and are typically the first to show consumer stress (people will skip a credit card payment before an auto or home). Above 4% is a reason for concern.

Delinquency rates can vary over time due to economic conditions, changes in lending standards, and other factors. “Generally”:

I’m not sounding an alarm here but rather, “let’s watch this”. Rate cuts could easily reverse some of this if they happen but we need to wait and see as the Fed typically does very little in election years to not be accused of being political in its actions.

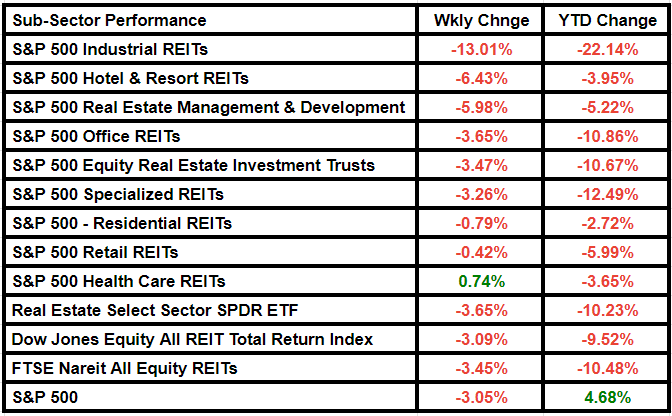

- 04/20/2024 – Real estate stocks continue on downward trajectory as market’s April pullback intensifies | Seeking Alpha

Funds continued to flow out of The Real Estate Select Sector SPDR Fund ETF, indicating pessimism in the investor community.

XLRE saw net outflows of ~$32.69M this week, compared to outflows of ~$100.35M last week, according to the data solutions provider VettaFi.

Seeking Alpha’s Quant rating system continues to grade the ETF as Strong Sell, while SA analysts continue to rate the fund as Buy.

- 04/20/2024 – Big Stocks Won When Markets Rose. They Are Winning Again in the Selloff. – WSJ, High rates and war fears hit smaller stocks harder—driving an unusual split in two of the major U.S. indexe

The main cause is interest rates, plus more recently fears about a wider Middle East war. Both hurt smaller companies far more than bigger ones—and for some bigger companies, higher rates even boosted the bottom line.

The impact of higher rates is part of the two-speed economy that has resulted from sharp rate rises, and then this year the evaporation of hopes for multiple rate cuts. Big companies are insulated from the impact of higher rates because they used their easy access to bond markets to lock in superlow-cost debt for a long time when rates were low. Many of the very biggest, particularly Big Tech stocks, are also sitting on huge piles of cash, which are earning more thanks to rate rises.

By contrast, smaller firms find it hard to issue bonds and borrow far more at a floating rate. As with poorer consumers who borrow on their credit cards, the cost of this debt has soared as the Fed tightened, hitting the profits of smaller companies. Goldman Sachs analysts calculate that almost a third of Russell 2000 debt is at a floating rate, compared with 6% for the S&P 500.

On top of that, smaller companies as a group have higher debt compared with earnings and more volatile earnings—making them less appealing when there is a flight to quality amid war fears.

- 04/20/2024 – Here’s What Higher for Longer Means for the Stock Market – WSJ Stocks are still trading near record levels, but some investors say further gains may be more difficult

The small-cap focused S&P 600 index tumbled 3% last week. That included a 2.9% drop on Wednesday after the inflation report, the largest one-day percentage decline since February. Small-caps, which tend to derive most of their revenue from inside the U.S., are especially sensitive to the trajectory of the economy.

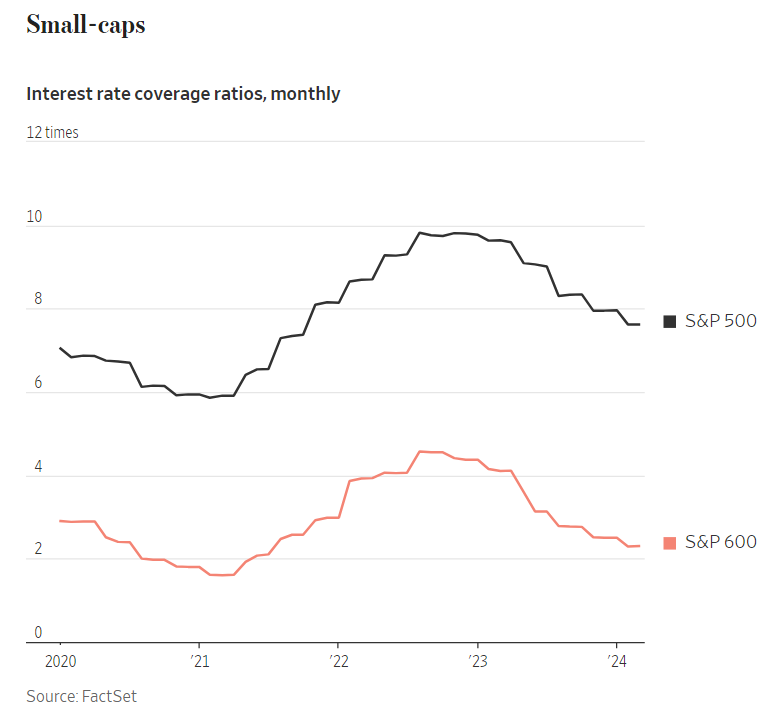

One big reason: Small stocks generally devote a much larger share of operating profit to covering interest on debt than larger ones do. The ratio of operating income to interest expense within the S&P 600 was 2.3 times as of March, according to Dow Jones Market Data. That compares with 7.6 times for S&P 500 companies.

They generally issue more floating-rate debt than bigger companies, so their loan payments fluctuate with benchmark interest rates. When rates go up, that means higher interest expenses dent their bottom lines and leave them more at risk of defaults.

About 44% of debt among companies within the Russell 2000, another small-cap index, was floating-rate at the end of last year, compared with 10% for the S&P 500, according to data from Lazard Asset Management.

Adding to the crunch: About 40% of the companies in the Russell 2000 didn’t turn a profit over the past year, compared with 10% in the S&P 500, according to J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

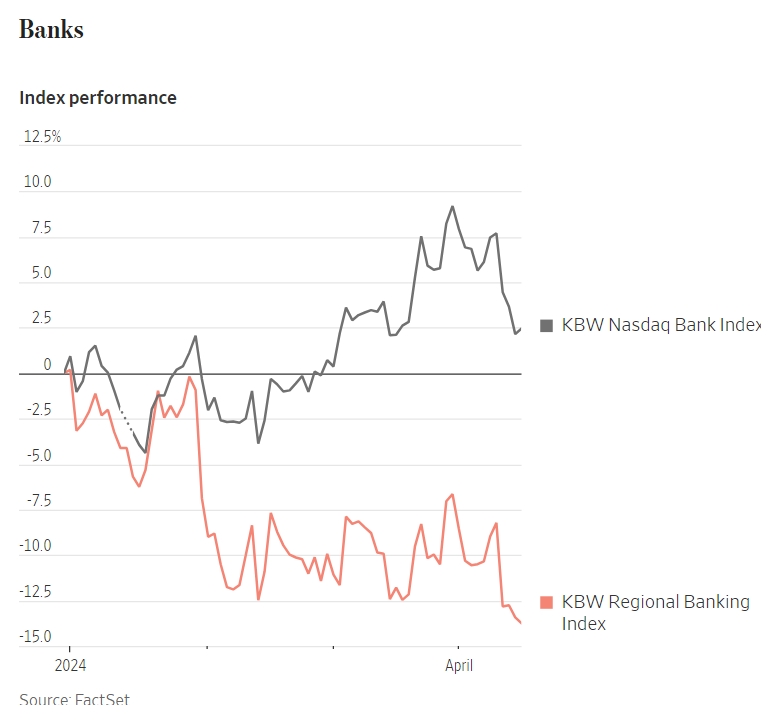

Higher interest rates propel depositors to move money to Treasurys and money-market funds for higher returns, contributing to lower deposits at banks. Meanwhile, banks have had to shell out more interest to yield-hungry depositors, particularly hurting the bottom line at small and midsize banks. Wells Fargo said Friday it expects net interest income, or profit from lending, to decline by 7% to 9% in 2024.

Delinquency rates could also creep higher if interest rates remain high, which could increase loan losses for banks.

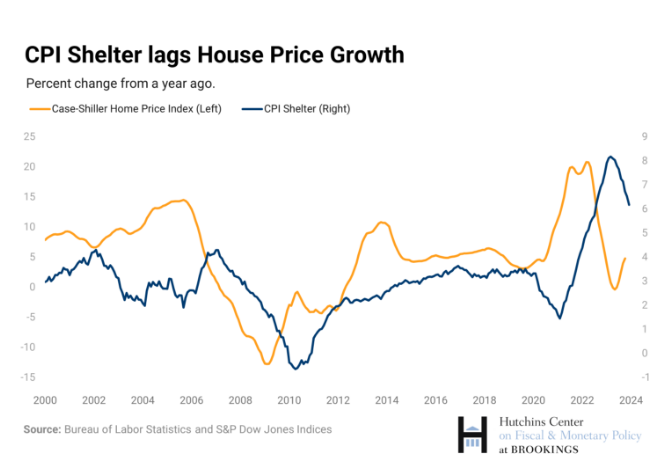

Higher interest rates have also pushed up mortgage rates back toward 7%, a level they haven’t seen since December. That has kept many would-be home buyers on the sidelines, leading to sharp declines in mortgage activity at the big banks, a source of revenue.

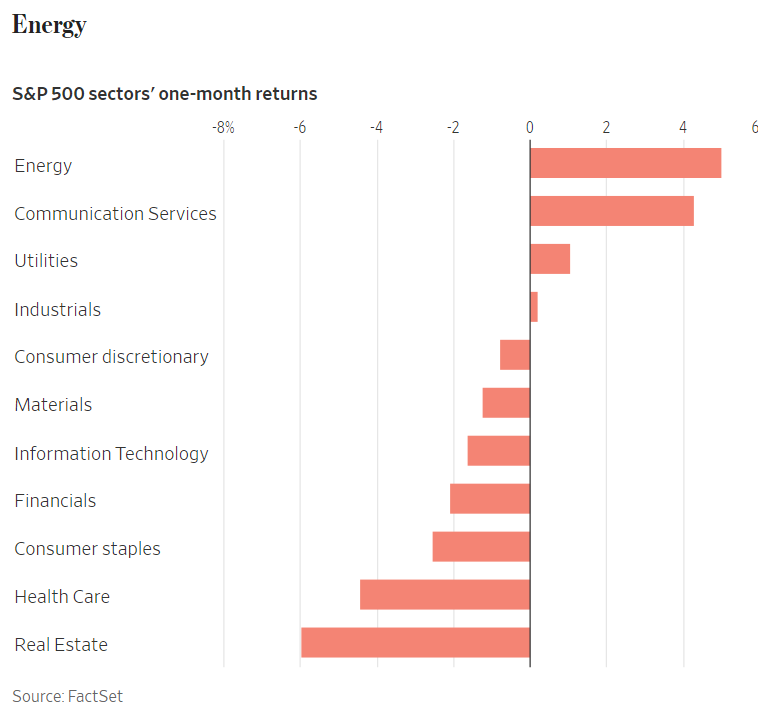

The S&P 500’s real-estate sector is down 8.8% this year, the worst performer of the 11 segments and the only group in the red.

The rate whipsaw has hit smaller banks harder than big ones. The KBW Nasdaq Bank Index, which includes heavyweights such as JPMorgan, has advanced 2.5% this year, while an index of regional banking stocks is down 14%.

Shares of oil-and-gas companies are making another run after being among the top performers in 2022. Rising oil prices boost revenue for oil-and-gas providers, while big companies in the sector trade at a discount to the overall market. Exxon and Chevron trade at about 13 and 12 times their earnings over the past 12 months, respectively; the S&P 500 trades at roughly 20 times.

The S&P 500 energy sector is up about 5% over the past month, beating every other corner of the broad index.

- 04/20/2024 – Fed Chair Jerome Powell Dials Back Expectations on Interest-Rate Cuts – WSJ, Inflation and hiring have been firmer than expected this year, weakening the case for pre-emptive rate reductions

The Fed’s preferred gauge, which will be released next week by the Commerce Department, is likely to show core prices rose 2.8% in March from a year earlier, the same as in February, according to estimates by Fed economists. But Powell said three- and six-month annualized inflation rates were now running above that level, underscoring how recent data have gone in the wrong direction. The Fed targets 2% inflation over time.

After last week’s CPI report, most analysts on Wall Street changed their forecasts, scrapping expectations of a June rate cut. They see the Fed waiting until July, September or December to start lowering rates, and they expect just one or two cuts this year.

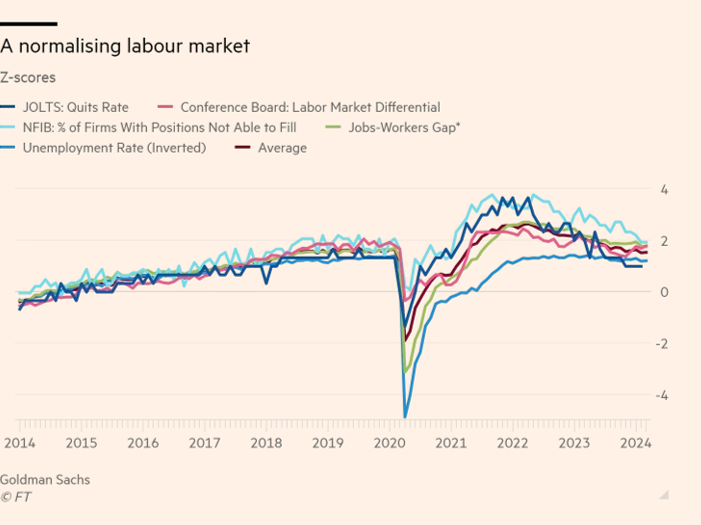

The Fed raised rates aggressively over the last two years to combat inflation, which soared to a 40-year high. But Powell in recent months has approvingly cited signs that labor market imbalances are easing. By maintaining that message on Tuesday, Powell suggested the Fed was only partially resetting its outlook.

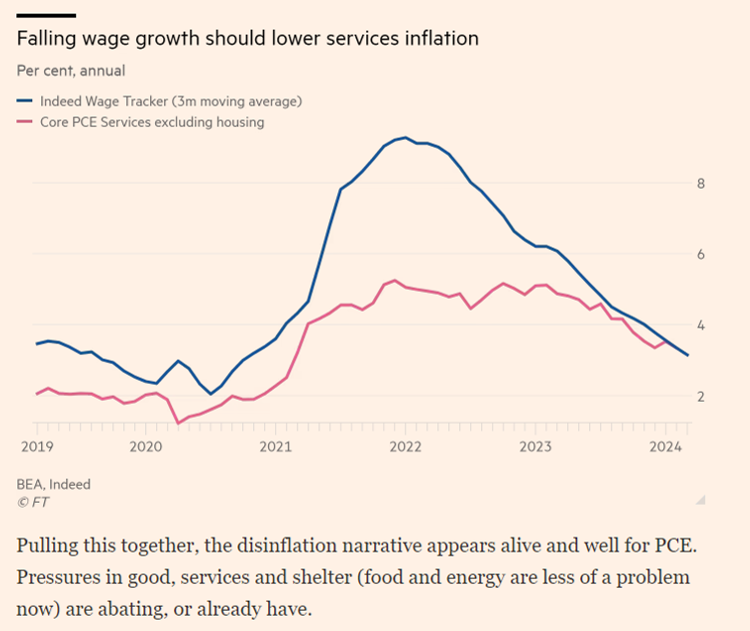

A continued slowdown in wage growth is a likely requirement for policymakers to remain confident that inflation will improve over time. Wage pressures “continue to moderate, albeit gradually,” Powell said.

- 04/02/2024 – Next Fed Rate Cut Could Be Delayed to March 2025 If PCE Inflation Stays High (businessinsider.com)

- If the Federal Reserve can’t cut interest rates this June, it might delay easing until March 2025, Bank of America said.

- Stubbornly high PCE inflation readings might make it difficult to lower them in June as many expect.

- BofA still expects three rate cuts this year, but says the next PCE readings will determine this.

Monetary easing by June is looking more and more like an out-of-reach dream, tempered by the latest batch of strong economic data.

After data Monday showed the ISM Manufacturing Index expanding for the first time since 2022, odds of a June interest rate cut briefly fell under 50%, according to Bloomberg data. And recent inflation figures — though in line with expectations — also give the Federal Reserve no reason to hurry.

But if the central bank doesn’t lower rates by June, it’s likely to hold off on any cuts until March 2025, Bank of America wrote on Tuesday.

The reason? The Fed officially targets the annual change in the personal consumption expenditures, which may make it harder to justify a cut later in the year.

That’s because comparisons with last year’s figures mean that year-over-year core PCE inflation is unlikely to decline further in the second half of 2024.

“Base effects for year-over-year core PCE inflation are favorable through May, but unfavorable for six of the last seven months of the year,” analysts said in a note. “If the Fed tells markets that a rate cut is not justified in June (by which time it will have the May CPI data in hand), it will be difficult to justify a cut later this year, when y/y core PCE inflation is likely to be flat or slightly rising, even if the three- and six- month rates are falling.”

Bank of America

In that case, Bank of America estimates that March is the Fed’s next best option. However, analysts did note that the central bank could still cut in June, followed by just one or two rate cuts this year.

- 04/02/2024 – Market Reacts: Less Than 50% Probability of June Rate Cut Following Strong Factory Data (msn.com)

- Anticipation of a June rate cut in the bond market dropped below 50% following strong factory data, according to Bloomberg.

- ISM manufacturing data showed expansion on Monday, the first in 16 months.

- Inflation aligns with Fed hopes, creating a “wait and see” situation for rate cuts, a former Fed official said.

Bond-market expectations of a rate cut in June experienced a notable setback on Monday, driven by the release of fresh factory data that pushed the odds of a rate cut below the 50% mark, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing index delivered a surprise to analysts and investors alike by surpassing expectations. It revealed an expansion in manufacturing activity for the first time since 2022, marking a significant turnaround from 16 consecutive months of contraction. This uptick was propelled by a sharp increase in both production and new orders, signaling resilience and vigor in the industrial sector. The robust performance of the manufacturing index serves as yet another testament to the enduring strength of the U.S. economy, prompting speculation about the necessity of immediate policy adjustments by the central bank.

- 04/01/2024 – The market sees a less-than-50% chance of a June rate cut after hot factory data (msn.com)

- Bond-market expectations of a June rate cut fell below 50% after strong factory data, according to Bloomberg data.

- ISM manufacturing data showed an expansion on Monday for the first time in 16 months.

- Inflation is in line with Fed hopes, but creates a “wait and see” situation for rate cuts, a former Fed official said.

The ISM manufacturing index came in hotter than anticipated, showing expansion for the first time since 2022. A sharp rise in production and new orders fueled the gauge’s bounce back, ending 16 months of contraction.

ISM Manufacturing Index March 2024: Factory Activity Unexpectedly Expands – Bloomberg

Powell says February’s PCE inflation data was ‘in line with expectations’ (marketwatch.com)

- 03/29/2024 – Fed’s Favored Inflation Gauge Rose to 2.5% in February – WSJ, The overall PCE price index was in line with expectations

A key measure of U.S. inflation rose as expected in February, putting a spotlight on whether price growth will be cool enough this spring to justify an interest-rate cut by midyear.

The overall personal-consumption expenditures price index rose 2.5% over the 12 months through February, the Commerce Department said Friday. That was in line with forecasts from economists polled by The Wall Street Journal. Core prices excluding volatile food and energy prices rose 2.8%, also in line with forecasts.

“It’s good to see something coming in in line with expectations,” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said Friday during a question-and-answer session at the San Francisco Fed.

From January to February, the PCE price index increased 0.3%, less than the 0.4% increase economists expected. The core index rose 0.3%.

Traders were pricing in a 64% chance the Fed will move to cut rates by June as of Thursday afternoon, according to CME Group.

He also said the Fed’s interest-rate setting has left the central bank in a good position to react to a range of different paths for the economy. That includes the possibility of cutting rates more than anticipated if the economy slows sharply or holding them at their current level for longer if inflation doesn’t slow as much as expected, he said.

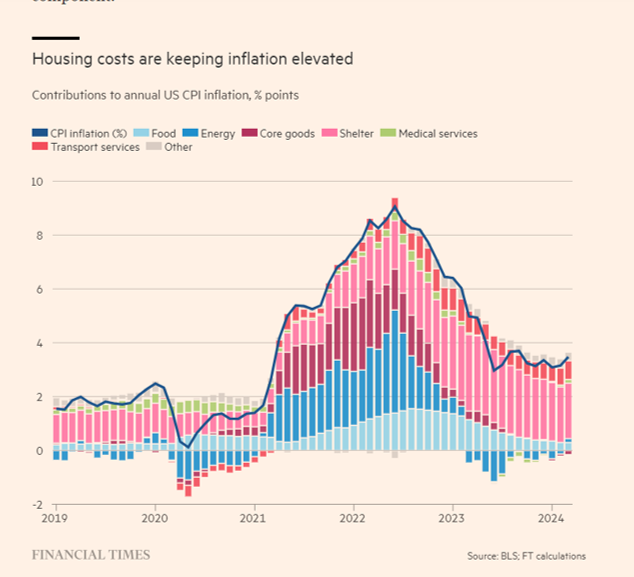

Inflation Victory Is Proving Elusive, Challenging Central Banks and Markets – WSJ, In the U.S. and Europe, underlying inflation has stopped falling or edged higher recently, weakening the case for rate cuts

Inflation is proving stickier than expected in the U.S. and Europe, creating a headache for central bankers and sowing doubts on whether investors are too optimistic about the world economy.

The decline in inflation from highs of around 9% to 10% across advanced economies in 2022 represent the easy gains, as supply-chain blockages eased and commodity prices, especially for energy, normalized.

The “last mile” is proving tougher. Underlying inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, slowed to 3% in the second half of last year across advanced economies but has since moved up to 3.5%, according to JP Morgan estimates.

That is forcing investors to rethink bets that inflation would steadily decline to central banks’ targets, generally around 2%. There are even concerns it could surge again, mirroring the second wave that characterized the high inflation of the 1970s.

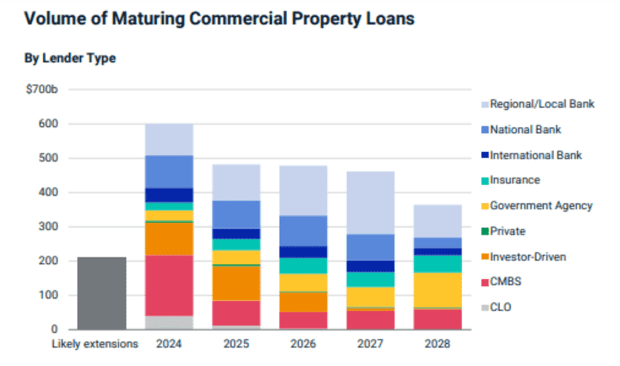

- 03/22/2024 – A $600 billion problem lurks in commercial real estate as Fed mulls when to cut rates (marketwatch.com)

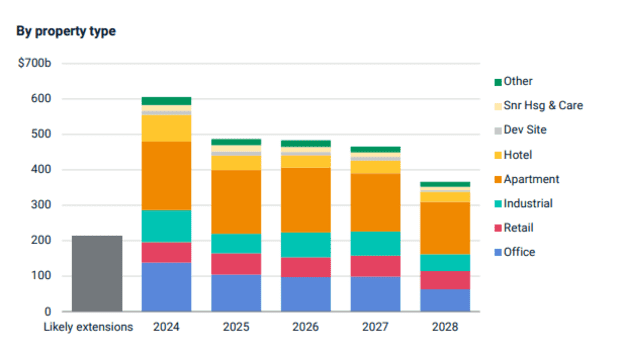

Wall Street’s bond machine and banks are responsible for big slices of at least a $600 billion wall of commercial real-estate debt coming due this year, according to MSCI.MSCI

Landlords with big bills coming due on commercial buildings will be listening closely to what Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has to say about interest rates Wednesday afternoon.

With deal activity depressed, property values sagging and at least $600 billion of maturing mortgage debt this year, the potential for more weakness in the banking sector has been a clear focus for regulators.

To help illustrate the issue, MSCI has broken down how much CRE debt is coming due in the next few years, by lender and property type, a guide to where potential weakness might lurk.

Wall Street’s bond machine created a big slice of the overall debt coming due in 2024, but so did big and small banks. A closer look at the debt coming due shows that roughly $200 billion in 2023 was likely extended, kicking some problems down the road. By property type, the most debt this year will be coming due on apartment buildings, hotels and offices.

- 03/22/2024 – The Federal Reserve Could Ease This Anti-Inflation Policy Before Cutting Rates (msn.com)

- After the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee meeting this week, Chair Jerome Powell said the central bank could ease quantitative tightening “fairly soon.”

- Quantitative tightening is the practice of selling off securities or letting them mature in order to take money out of the marketplace and cool inflation.

- Economists think the Federal Reserve could begin easing that practice before they cut rates.

“While we did not make any decisions today on this, the general sense of the committee is that it will be appropriate to slow the pace of runoff fairly soon,” Powell said at the Wednesday press conference. “The decision to slow the pace of runoff does not mean that our balance sheet will ultimately shrink by less than it would otherwise, but rather allows us to project the ultimate level more gradually.”

Powell also said slowing the pace of tightening will reduce the possibility of stress on markets, hopefully helping to facilitate the soft landing the Fed has been looking for.

Economists said Powell’s comments indicate the Fed may taper quantitative tightening—possibly as soon as their next meeting in May—before they cut their influential fed funds rate, which market participants don’t expect will happen before June.

“We also keep our call for an announcement of tapering in May with an end to balance sheet runoff at year-end,” wrote economists at Bank of America after the meeting. “The risk to our view is that they start the rate cut cycle later and start taper later. Upcoming inflation data will be an important determinant of what comes next.”

While the latest data hadn’t given officials the confidence they would need to begin rate cuts, Chair Jerome Powell said his outlook for inflation to continue declining hadn’t changed substantially in recent weeks. The projections released Wednesday were little changed from December and showed most of his colleagues expect two or three cuts this year.

The central bank held steady its benchmark federal-funds rate in a range between 5.25% and 5.5%, a 23-year high.

Transcript: Fed Chief Jerome Powell’s Postmeeting Press Conference – WSJ

Jerome Powell says risks of Fed achieving dual mandate find better balance | Seeking Alpha

Fed still expects three rate cuts in 2024, but fewer cuts in 2025, dot plot shows | Seeking Alpha

- 03/19/2024 – The Fed Is Playing a Waiting Game on Rate Cuts. The Rules Are Starting to Change. – WSJ While investors focus on whether officials project fewer rate cuts, the Fed looks ahead to recession risks

- 03/16/2024 – Fed rate cuts will be a tailwind for small caps, says Fundstrat’s Tom Lee | Watch (msn.com), some positive comments for small stocks and banks, but need to wait for the 1st rate cut, nobody knows when it will come

- 03/16/2024 – Producer price index comes in hot in February, rising 1.6% Y/Y | Seeking Alpha

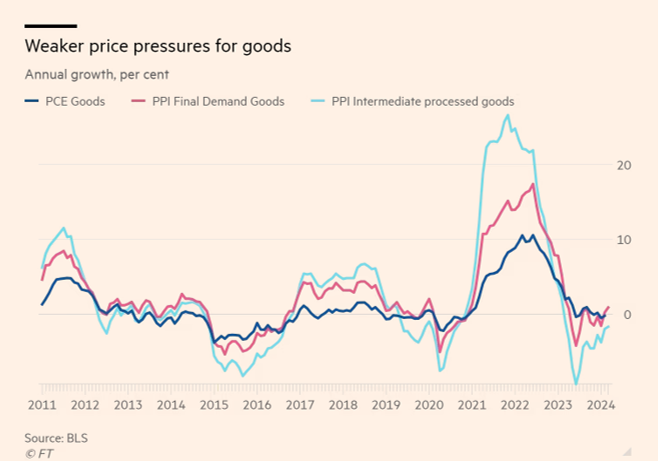

The Producer Price Index rose 0.6% from January, hotter than the +0.3% expected and following January’s 0.3% growth and December’s 0.1% increase, the U.S. Department of Labor said on Thursday.

Final demand goods prices staged their biggest jump, at +1.2%, since August 2023. Almost 70% of the increase is attributed to the index for final demand energy, which surged 4.4%.

Y/Y, the inflation gauge at the producer level increased 1.6%, compared with the +1.2% consensus and 1.0% prior (revised from +0.9%).

Core PPI, which excludes food and energy, grew by 0.3% vs. +0.2% expected and +0.5% prior (unchanged). On a Y/Y basis, that comes to a 2.0% rise, compared with the +1.9% consensus and 2.0% prior (unchanged).

While the print came in much higher than expected, “the good news is much of the producer inflation was outside of core inflation in food and energy, up 1.0% and 4.4%, respectively,” observed KPMG macroeconomist Megan Martin-Schoenberger in a post on X.

RSM U.S. Chief Economist Joseph Brusuelas also sees some good new underlying the Y/Y headline print. “Roughly one-third of the increase in the PPI was driven by a 6.8% increase in gasoline prices. Nearly 70% of the increase in final demand was due to a 4.4% advance in final energy demand,” he said on X. “If you’re managing a firm or portfolio, this is likely not to be repeated next month, so one should ignore the breathless declarations on financial television of a reacceleration of inflation.”

Prices for final demand services increased by 0.3% M/M after a 0.5% rise in January. The index for final demand services less trade, transportation, and warehousing advanced 0.5%. Prices for final demand transportation and warehousing services jumped 0.9%. Margins for final demand trade services, though, dropped 0.3%, the DOL’s U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics said.

Said TradeStation Global Head of Market Strategy David Russell, “We can tolerate a hot reading today because we still have a couple of months to right the ship before the Fed’s key June meeting.”

With traders’ eyes focused on inflation, with a view to the Federal Reserve’s next move in interest rates, the probability of a rate cut in May has slipped to 8.2% from 11.2% a day ago, while the odds of the federal funds rate staying at 5.25%-5.50% increased to 91.7% from 88.7%, according to the CME FedWatch tool.

For the Fed’s June meeting, the probability of the central bank holding rates rose to 35.8% from 34.8% a day ago. At the same time, the odds of a 25-basis-point rose to 59.1% from 58.2%. That reduced the chances of rates falling any further than 5.00% at the June meeting.

Producer Price Index News Release summary – 2024 M02 Results (bls.gov)

- 03/16/2024 – Suspense Builds for Fed as Growth Downshifts and Inflation Lingers – WSJ, Recent data call into question chances of Fed rate cuts this summer

The likelihood of a quarter-point cut by June, as implied by markets, has fallen to 50.4% from 57.4% a week ago, according to the CME FedWatch tool. The implied chance that the Fed could stand pat through its July meeting has risen to 24.1% from just 8.1% a week ago.

In a note on Thursday, Bank of America strategists argued that the macroeconomic picture is “flipping from goldilocks to stagflation,” which they defined as growth below 2% and inflation of between 3% and 4%. They highlighted trades that could benefit from stagflation such as gold, crypto and cash.

But investors should keep the bigger picture in mind. Growth, while coming off the boil, is still solid. And inflation is well below where it was just a few months ago. Taking into account the latest consumer and producer inflation readings, economists at Goldman Sachs inched up their estimate for the February core personal-consumption expenditures price index, the inflation measure favored by the Fed, by 0.02 percentage point. They now expect it rose 2.8% in February from a year earlier. That would be unchanged from January, but down from 3.2% as recently as November. Meanwhile they expect first-quarter gross domestic product growth of 1.7% on an annualized basis, down from an earlier estimate of 2.1%.

- 03/13/2024 – seeking alpha’s discussion on CPI and PCE

PCE January 2024: Spending And Inflation Still Too Strong For Fed | Seeking Alpha

CPI February 2024: No Fed Rate Cuts Any Time Soon | Seeking Alpha

Yesterday’s inflation report had no surprises for me.

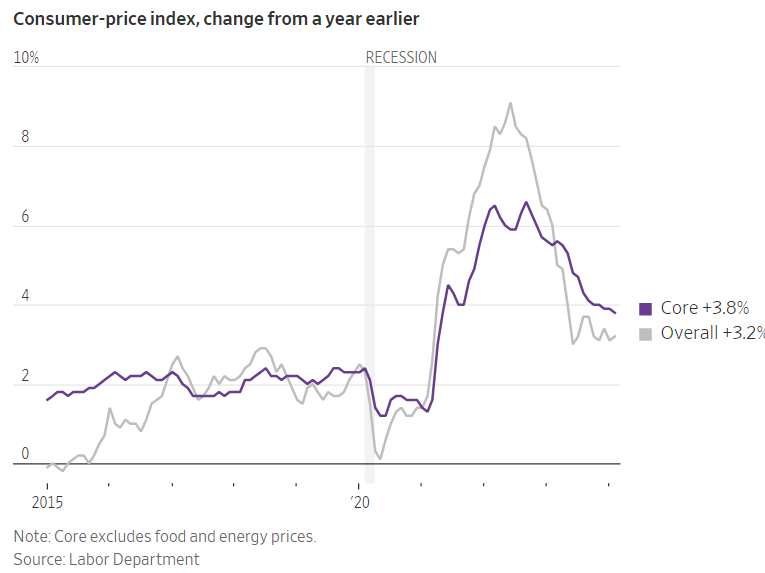

Consumer prices were up 3.2% last month from a year earlier – up a hair from expectations of 3.1%.

It’s the second straight month of higher-than-expected inflation, but investors still expect the Federal Reserve to start cutting rates later this year (with the first cut expected in June).

Here’s the Wall Street Journal with more: Inflation Picks Up to 3.2%, Slightly Hotter Than Expected. Excerpt:

[Officials] are focused on when to cut rates – rather than whether to raise them again. Inflation has declined notably from 40-year highs following the most rapid rate increases in four decades.

Tuesday’s report “basically tells the story that there’s a gradual improvement” in core inflation, [Eric] Rosengren said in an interview. “As long as wages and salaries continue to drift down, I don’t see this report really altering the overall view of probably a June reduction.”

As I’ve been writing for the better part of a year, I continue to believe that inflation is a nonissue and will remain in the 3% to 4% range.

While this is higher than the Fed’s official target of 2%, I think, unofficially, the Fed (and investors) will have no problem with this modest level of inflation.

The Consumer Price Index advanced 0.4% in February, matching the 0.4% increase expected and slightly accelerating from the 0.3% rise in January (unrevised), the Department of Labor said on Tuesday.

“The slightly stronger than expected CPI doesn’t do much to add to [the Federal Reserve’s] confidence, but they can still ponder the possibilities for May, June, and July,” said Mark Hamrick, senior economic analyst at Bankrate.

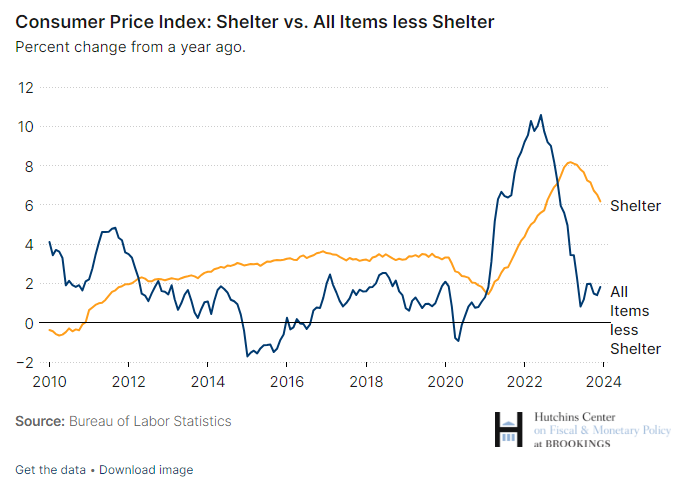

Shelter and gasoline prices contributed the most the the monthly increase, accounting for more than 60% of the monthly increase in the index of all items.

Also boosting the headline number, the energy index increased 2.3% over the month, with all of its components indexes rising. The food index, as well as the food at home index stalled, but the food away from home index edged up 0.1%.

On a Y/Y basis, the measure rose 3.2%, more than the 3.1% pace expected and +3.1% in the prior month. Though down significantly from the mid-2022 inflation peak, the annual pace remains well above the Fed’s 2% target as policymakers are set to gather in a week to discuss whether interest rates should stay higher for longer.

Excluding food and energy, core CPI increased 0.4% vs. +0.3% consensus and +0.4% prior. Y/Y, core inflation gained 3.8% vs. +3.7% expected and +3.9% prior.

Among the index contributing to the monthly core print include shelter, airline fares, motor vehicle insurance, apparel, and recreation, the DOL said. The index for personal care and the index for household furnishings and operations were among those that retreated.

Consumer Price Index Summary – 2024 M02 Results (bls.gov)

- 03/12/2024 – Inflation Picks Up to 3.2% in February, Slightly Hotter Than Expected – WSJ A focus at the next Fed meeting will be whether most officials continue to expect three cuts this year—or fewer

U.S. inflation was slightly stronger than expected last month but did little to change expectations that the Federal Reserve will begin cutting rates later this year.

Consumer prices rose 3.2% in February from a year earlier, the Labor Department said Tuesday, up slightly from economists’ expectations of 3.1%.

The second straight month of firmer-than-expected inflation is likely to reinforce the central bank’s wait-and-see posture toward rate reductions when officials meet next week. Still, officials are focused on when to cut rates—rather than whether to raise them again. Inflation has declined notably from 40-year highs following the most rapid rate increases in four decades.

Eric Rosengren, who headed the Boston Fed from 2007 to 2021, said the Labor Department’s reading shouldn’t fundamentally alter expectations for three rate cuts this year, as officials penciled in at their December meeting. Investors expect the first rate cut in June.

Core prices, which exclude food and energy items in an effort to better track inflation’s underlying trend, rose more than expected, both when measured from a year ago and a month ago.

Tuesday’s report “is likely to instill less confidence at the Fed that inflation is fast approaching its 2% target,” said Barclays U.S. economist Pooja Sriram.

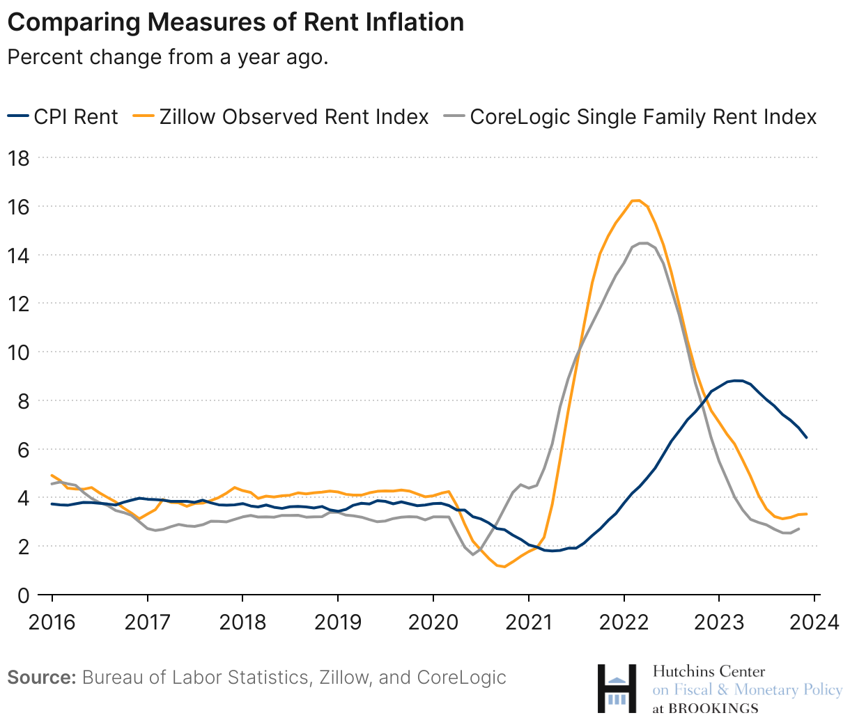

A recent BLS email indicated that the “weights for single family detached homes increased materially from December 2023 to January 2024,” and that analysts trying to understand why OER had increased so much more than rent in January 2024 had found “the source of the divergence.” That email was retracted less than two hours later. The whole episode raised many more questions than it answered, so the BLS released another statement to try to clarify things. In that statement, the BLS noted that the share of single-family detached (SFD) units within OER increased by five percentage points in January 2024.

In my view, the latest BLS statement on the reweighting of SFD units within OER does not imply that OER will be structurally higher than rent going forward.

the large spread between rent and OER, which was largely due to a jump in the South’s smaller B/C cities, may just reflect monthly noise in the smaller sample cities.

Below is a chart of the Z-score of the spread (NSA rent MoM% minus NSA OER MoM%), with the data covering January 1998 to now. This January was clearly a big move, and it’s one of the few moves exceeding 3 standard deviations over this timeframe, but it’s not the only one. Additionally, there have been some other large moves, with one as recently as July 2021 (when NSA rent was 18bs and OER was 30bps). Note that on the occasions that we’ve seen some volatile moves in the rent-OER spread, including as recently as July 2021, the spread narrowed sharply in the following month or two. In six instances selected from the chart below, the absolute average spread between rent and OER was 19bps, but it narrowed to an average of 6bps in the following month. Thus, I would expect the January 2024 spread to narrow sharply in the next month or two, with OER sliding down to a pace closer to rent.

Bilello also highlighted an interesting data point that reinforces my view that a recession isn’t imminent:

The Conference Board, who previously predicted a recession would begin in Q1/2/3/4 2023 and then Q1/2 2024, is no longer forecasting a downturn.

Why?

6 out of the 10 components in their index have turned positive over the last 6 months, led by the surging stock market.

And here’s the relevant chart he included: